How to Control Mealybugs in Greenhouses and Nurseries

Mealybugs (Pseudococcidae) are among the most persistent and destructive pests in greenhouse and nursery production. They infest hundreds of plant species, from ornamental plants to fruit and vegetable crops, and their impact can be severe. In ornamental plants, heavy infestations can reduce marketable yield by 15–20%. High-value crops such as citrus or grapes may suffer economic losses in the thousands of dollars per acre.

Their resilience is largely due to biological adaptations. Mealybugs have a dense waxy coating that shields them from pesticides, they feed in concealed areas such as leaf axils and root zones, and they reproduce quickly in warm, protected environments. In greenhouses, they can complete six to eight overlapping generations per year, making early detection and a coordinated control strategy essential.

Identification and Life Cycle

Mealybugs are small, soft-bodied insects ranging from 1 to 4 millimeters (0.04-0.16 inches) in length. They have oval, segmented bodies, covered with a white, cotton-like secretion. In many species, lateral wax filaments extend from the sides of the body, and some, such as the striped mealybug (Ferrisia virgata), have long caudal filaments at the rear.

Females are wingless and long-lived, while males, present in some species,are winged, short-lived, and do not feed. Depending on the species, females lay between 50 and 600 eggs in cottony sacs, or they give birth to live young. Eggs hatch within six to fourteen days at optimal conditions of 25-27°C (77-80°F) and 60-70% relative humidity. Development from egg to adult may take 30 to 70 days, depending on temperature, and overlapping generations are common.

Several species are important in greenhouse and nursery systems, including the citrus mealybug (Planococcus citri), Madeira mealybug (Phenacoccus madeirensis), striped mealybug (Ferrisia virgata), Mexican mealybug (Phenacoccus gossypii), and root-infesting species such as Ripersiella hibisci and Rhizoecus spp.

Why Mealybugs Are Difficult to Control

The waxy coating of mealybugs can reduce pesticide penetration by as much as 70% in adult stages compared to crawlers. Their habit of feeding in hidden plant structures further limits pesticide contact. Mealybug populations usually contain all life stages at once, so a single treatment rarely eliminates an infestation. In addition, adults may feed intermittently, reducing the uptake of systemic insecticides. In warm greenhouse environments, populations can rebound from low numbers in less than four weeks if management is inconsistent.

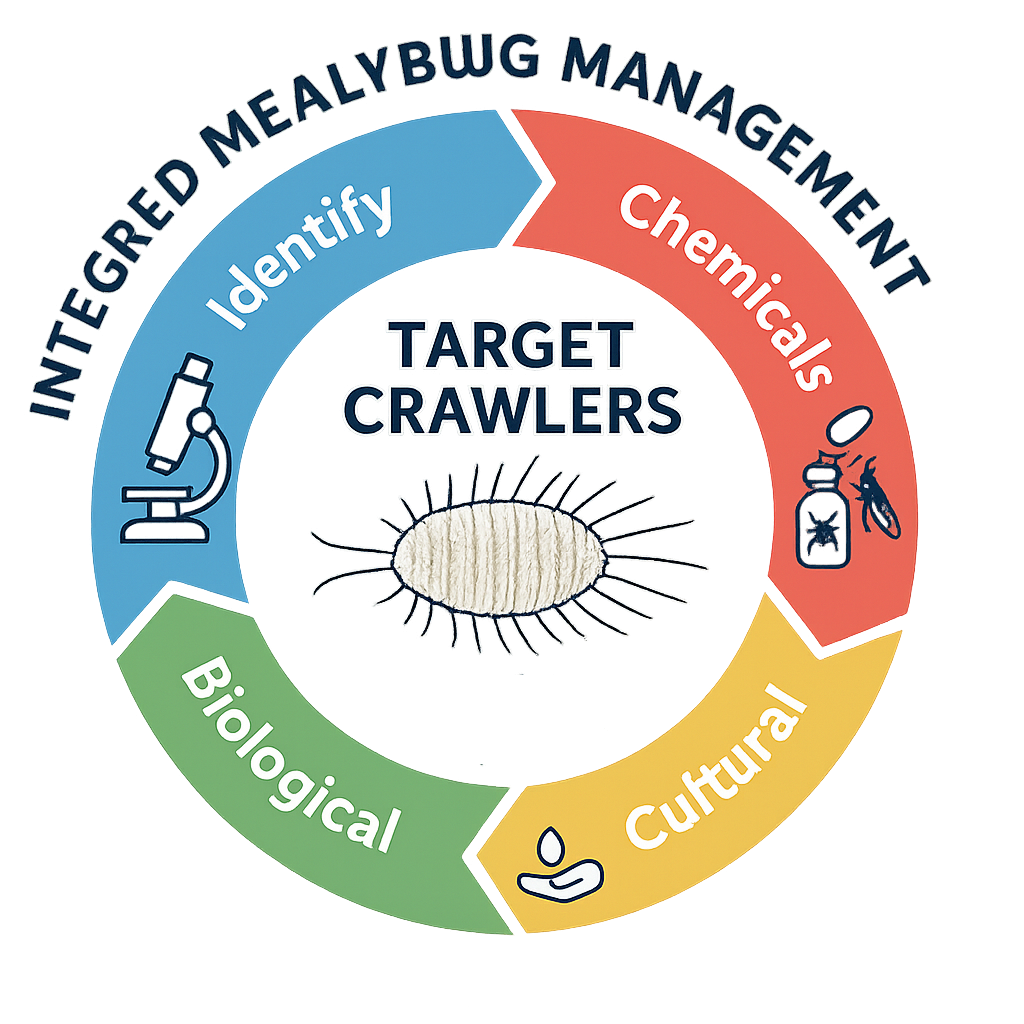

Strategies for Effective Control

Successful control begins with accurate identification of the species present. Morphological examination of antenna segmentation, wax filament patterns, and body shape can be used, and molecular diagnostics are useful for confirmation in difficult cases. Monitoring is critical. Weekly inspections of vulnerable plant parts and the use of sticky traps for male mealybugs can help detect infestations early. Crawler activity can be tracked with double-sided sticky tape near infested areas, allowing treatments to be timed for maximum effect.

Chemical control remains an important part of integrated management, but resistance prevention requires rotation between different insecticide modes of action.

Systemic insecticides:

- Dinotefuran – neonicotinoid, IRAC Group 4A

- Flupyradifurone – butenolide, IRAC Group 4D

- Thiamethoxam – neonicotinoid, IRAC Group 4A

Contact insecticides:

- Acephate – organophosphate, IRAC Group 1B

- Bifenthrin – pyrethroid, IRAC Group 3A

Insect growth regulators:

- Buprofezin – IRAC Group 16, disrupts molting

Lipid biosynthesis inhibitors:

- Spirotetramat – IRAC Group 23, effective against root mealybugs

Control improvement: Combining systemic and contact insecticides in rotation can increase overall control by up to 35% compared to using either type alone.

Timing is crucial. Applications should be made when crawlers are emerging, before the wax coating becomes thick. Spray coverage must be thorough to reach hidden insects, and for root mealybugs, soil or substrate drenches improve systemic uptake. The use of adjuvants or penetrants can further enhance coverage and wax penetration.

Biological control can provide valuable long-term suppression, especially under stable greenhouse conditions. The predator Cryptolaemus montrouzieri (the mealybug destroyer), can consume over 250 mealybugs or egg sacs in its lifetime. Parasitoid wasps such as Anagyrus pseudococci and Leptomastix dactylopii are effective against certain species, although their performance varies with climate and host density.

Cultural practices play a vital role in prevention and containment. These include quarantining new plant material, removing heavily infested plants, pruning and destroying infested plant parts, disinfecting tools, and minimizing human-assisted spread through clothing and handling. Studies have shown that removing as little as 5–10% of heavily infested plants early can prevent infestation from spreading to an entire crop.

Regulatory Compliance

Growers must comply with local and national pesticide regulations, including label restrictions on application rates, maximum number of applications, Restricted Entry Intervals (REIs), and Pre-Harvest Intervals (PHIs). Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) for edible crops vary by country, and some active ingredients, such as certain neonicotinoids, are restricted or banned in regions like the European Union. Misuse of pesticides can result in rejected shipments, legal penalties, and environmental harm, so label adherence and consultation with regulatory bodies are essential.